Art Thoughts #1: Revelations, Memory Drawing and Bargue Plates

Observation and Learning to Improve Proportion

A couple of weeks ago, I completed a personal painting for the first time in a while. It made me realize that I need to step back and focus on improving my drawing skills, especially when it comes to proportions. But how do you improve proportion? Should I memorize proportion charts, and keep drawing from observation until I get it, or is there something I’ve been missing this whole time?

There I was, feeling confused and directionless, looking for study plans or books, until I rediscovered Charles Bargue's “Drawing Course” saved on my PC. If you’re unfamiliar, it is a classical drawing study program developed in 19th-century France for students to learn fundamental drawing skills. (You can find it for free in the Internet Archive.)

I never took it seriously, having started with Russian Academic drawing. In comparison, I was taught that all you need is to focus on construction, drawing through like an X-ray and keeping your perspective solid. Bargue, on the other hand, along with a few Western art schools, seemed to favor shape versus form in their studies. And while that difference helped me improve at a fast pace, it also left me perplexed about how to get the most out of the drawing for the painting.

I would keep pushing the drawing and construction but when it was time to paint, I didn’t always know how to get from my construction to appealing shape design in the final painting. When I asked my peers, nobody knew exactly what I meant by ‘how to marry drawing and painting’ or ‘how to go from drawing to painting’.

As a result of my weak drawing skills, I had an easy time painting pretty well from reference (spending hours and hours trying to get proportions right) but struggled a lot with imaginative work. And I still struggle.

However, I found an explanation as to why I never learned proportion despite doing thousands of timed gesture drawings and photo studies. Can you guess what it is?

Memory Drawing

I don’t remember how I found this book but I couldn’t stop reading the first chapter of it. It talked about the history of memory drawing. I didn’t think much of it until it mentioned Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran or Père Lecoq. The man was a French artist and teacher who wrote a famous book on memory drawing in the mid-nineteenth century. And what impressed me was this exact story:

Copying in the Louvre was a time-honored tradition and many would say a necessary step in an artist’s training. Boisbaudran agreed and required his students to do some of their Louvre copies via their memory. In fact, when asked to prove his method to the Commission of the École des Beaux-Arts, the task given to one of his students, Georges Bellenger, was to go to the Louvre and memorize Titian’s A Woman at Her Toilet (the painting was then known as the portrait of Laura de Dianti). He was to draw it from memory, directly in front of the Commission. Below is his result, on the left, and the original Titian on the right.

"I have to do it," I thought. Not much further in the book it talked about a different approach I’ve never heard about. The Cavé Method.

Developed by Marie Elisabeth Blavot Boulanger Cavé as a set of lessons for young children, the book received a magazine review upon publication stating, “Here is the first method of drawing that teaches anything.”

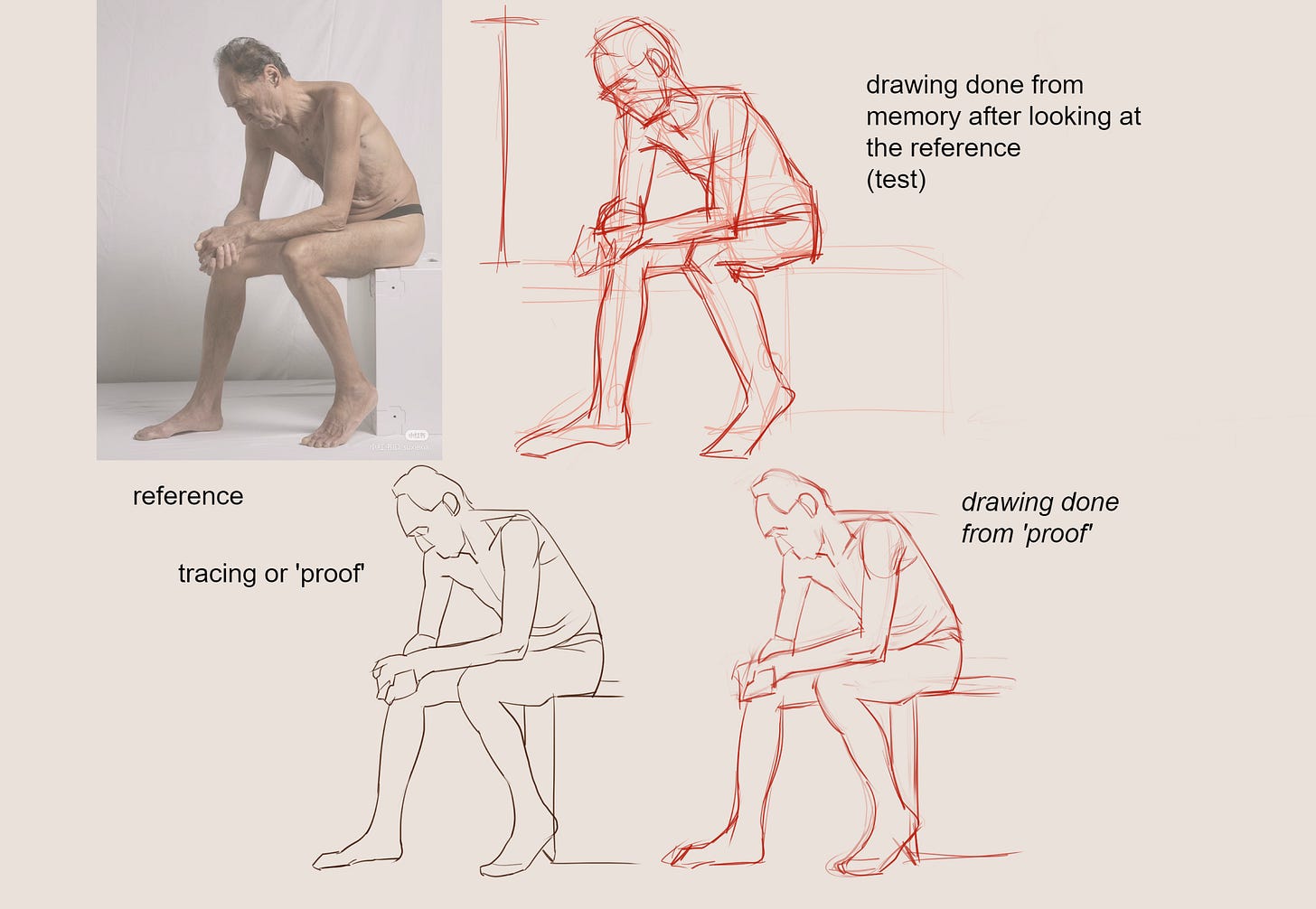

[…] she advocated that the student begin their studies by tracing the outline of the subject onto a piece of translucent gauze which had been stretched over a frame. The tracing becomes the proof. The student then tries to draw the subject, using the traced proof as a teacher, oftentimes overlaying the drawing with it to check for accuracy. The next step, to be done on the same day, was to redraw the subject from memory which was then also checked with the proof. Finally, later that evening, the student was to do yet another memory drawing of the same subject, only this time the proof was not to be used. The main goal, of course, was to teach the student to draw, as Delacroix stated in his review, “not the reproduction of the object as it is, [construction, perspective, etc.] but as it appears [to the eye].”

And what’s most interesting is that students following this method ended up learning perspective without studying any rules. So I tried it.

Ironically, I was trying so hard to get the perspective right, and I failed. Drew the head too big, and not inserted correctly, the left leg bit too short, the feet too big, and so on. It opened my eyes to how bad my eyeballing is (pun not intended). You should try it if you haven’t.

Remember Delacroix's quote from the Cavé Method review? “not the reproduction of the object as it is, [construction, perspective, etc.] but as it appears [to the eye].” The book later explains the difference, defining the types of perception as top-down and bottom-up processing.

With the preceding division in mind, the direct path to learning to draw is learning to perceive through direct observation. This path is considered to be bottom-up processing. In other words, the brain’s perception of the observed image begins with the observed image itself. Perception using the bottom-up model does not rely upon a visual understanding of what the object actually is (an apple, a chair, etc.). Rather, it is concerned with the visual properties of the object independent of the object’s classification.

As you already guessed, top-down processing is the opposite, or perception through the idea or a concept. “The idea can be based upon many things: construction, form, concept, anatomy, or any combination of them.“

While I still try to notice big silhouettes and positive/negative space, the rest of the time I observe in a top-down manner, e.g. my trail of thought often sounds like, ‘the spine goes there, ribcage could look like this box, arms insert here’ and so on. This might be why my proportion has been lacking.

Back to Practice

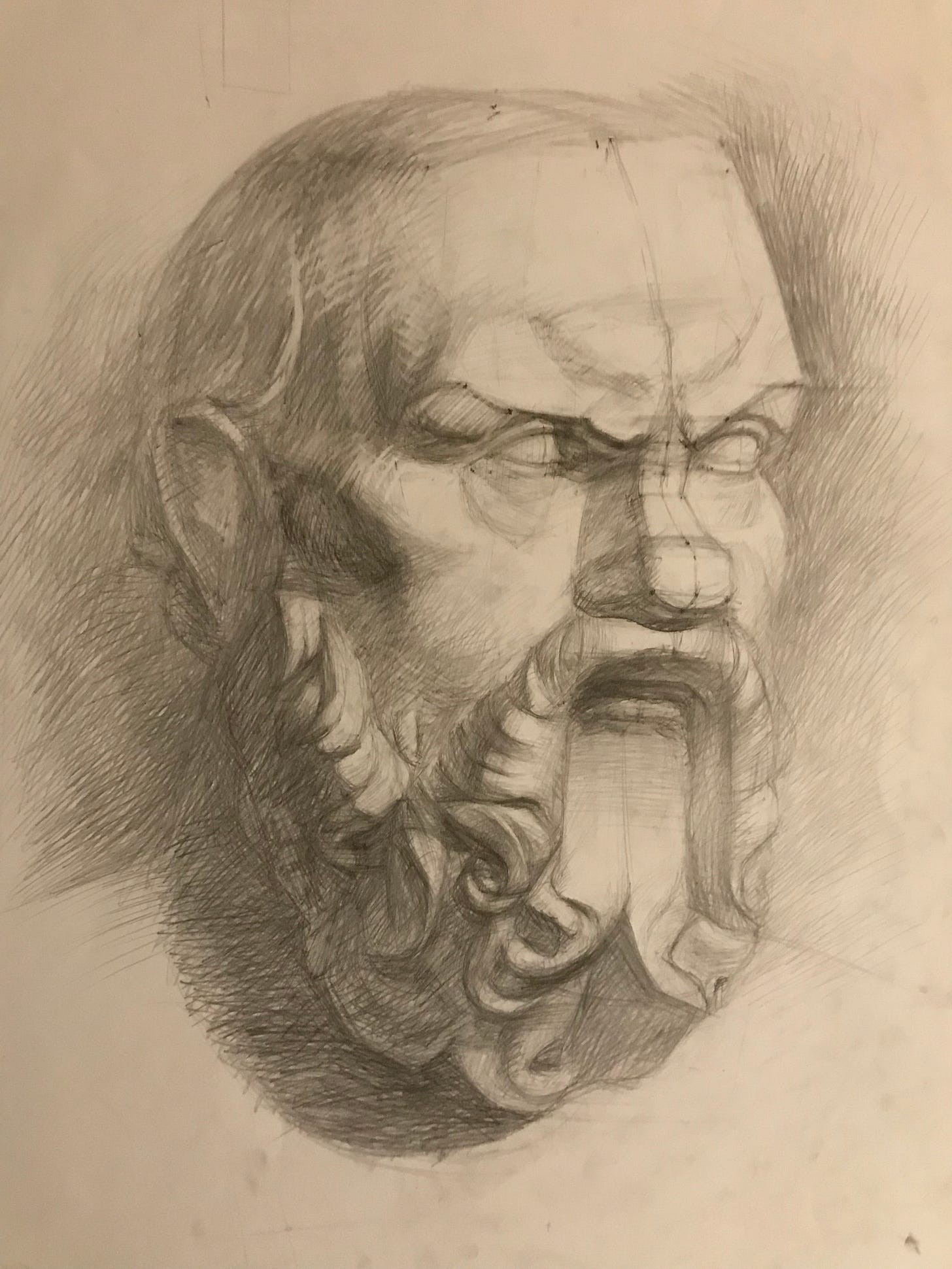

While I didn’t get to read more of the book yet, I started practicing memory drawing with the Cavé Method on my own. Conveniently, I’ve already done a few Bargue plates so it was a perfect opportunity to test how much information I retained from that practice. Here they are.

I compared it with ‘proof’ if the scribble looked wrong based on memory or I couldn’t remember parts of it. While it went well with foot plates, I didn’t remember anything from drawing the plates that included multiple small drawings (plates 1-4). Not to say that time spent on the drawing is the only factor.

Memory drawing helped me make more observations, and it also made it easier to store them in my visual library. And while I still don’t know what I’m doing, I’m sure I’m on the right track. The artists of the past have already figured it all out; they've got my back.